Articles on this page are available in 2 other languages:

Spanish (23), Chinese (Simplified) (7)

(learn more)

Overview

Brief Summary

The Cattle Egret (Bubulcus ibis)

is an Old World species that colonized northeastern South America from

Africa in the 1870s and 1880s (although it may not have actually

established until decades later), spread to Florida by the 1940s or

1950s, and reached California by the mid-1960s. More recently, it has

colonized the Australasian region. In the Western Hemisphere, the Cattle

Egret breeds locally from most of the United States (and adjacent

Canada) south (mainly in coastal lowlands) through Middle America, the

West Indies, and South America (including Trinidad and Tobago and the

Galapagos Islands) to northern Chile and northern Argentina; in southern

Europe, it breeds from the Mediterranean region east to the Caspian Sea

and south throughout most of Africa (except the Sahara), including

Madagascar and islands in the Indian Ocean. In Southeast Asia, it breeds

from India east to eastern China, Japan, and the Ryukyu Islands and

south throughout the Philippines and East Indies to New Guinea and

Australia. In the New World, Cattle Egrets winter throughout much of the

breeding range from the West Coast, Gulf Coast, and Florida in the

United States south through the West Indies, Middle America, and South

America. In the Old World, they winter from southern Spain and northern

Africa south and east through the remainder of the breeding range in

Africa and southwestern Asia and from southern Asia and the Philippines

south through Indonesia and the Australian region. The Cattle Egret was

introduced to the Hawaiian Islands in 1959 and is now established on

most of the larger Hawaiian Islands. The Cattle Egrets in Asia and

Australia are sometimes treated as a distinct species, the Eastern

Cattle Egret (B. coromanda), separate from the Western Cattle Egret (Bubulcus ibis).

Unlike other herons and egrets, this species typically feeds in dry fields, often following cattle or other grazing animals and waiting for them to flush insects. It also occurs in other open habitats, including aquatic ones. It nests in low trees and shrubs in mixed colonies with other species of herons and egrets. When associated with grazing cattle in fields, Cattle Egrets feed mainly on large insects flushed by the cattle, but in other situations they may eat crayfish, earthworms, snakes, nestling birds, bird eggs, and sometimes fish. They may also scavenge for food in garbage dumps. Although often associated with cattle or horses in North America, on other continents Cattle Egrets may follow elephants, camels, zebras, deer, and other grazers. They may also follow tractors and lawnmowers.

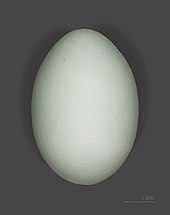

Cattle Egrets usually first breed at 2 to 3 years of age. The male establishes a pairing territory in or near the colony and displays there to attract a mate. Displays include stretching the neck and raising plumes while swaying from side to side, making short flights with exaggerated deep wingbeats. The nest site is typically in a tree or shrub in a heron rookery on an island or in a swamp. The nest is built mainly by the female using materials collected mainly by the male. It is a platform or shallow bowl of sticks, often with green, leafy twigs added. The typically 3 to 4 (range 1 to 9) eggs are pale blue. Incubation is by both sexes for 21 to 26 days. Young are fed by both parents (by regurgitation). The young begin to climb around near the nest at around 15 to 20 days, to fly at 25 to 30 days, and become independent around 45 days.

Cattle Egrets are strongly migratory. Birds from northern breeding areas in North America may winter to the West Indies, Middle America, and northern South America. In the United States, they are common year-round in Florida, along the Gulf Coast, and in parts of the Southwest. Young birds may disperse great distances, even thousands of kilometers.

(Crosby 1972; Maddock and Geering 1994; Kaufman 1996; AOU 1998; Dunn and Alderfer 2011)

Unlike other herons and egrets, this species typically feeds in dry fields, often following cattle or other grazing animals and waiting for them to flush insects. It also occurs in other open habitats, including aquatic ones. It nests in low trees and shrubs in mixed colonies with other species of herons and egrets. When associated with grazing cattle in fields, Cattle Egrets feed mainly on large insects flushed by the cattle, but in other situations they may eat crayfish, earthworms, snakes, nestling birds, bird eggs, and sometimes fish. They may also scavenge for food in garbage dumps. Although often associated with cattle or horses in North America, on other continents Cattle Egrets may follow elephants, camels, zebras, deer, and other grazers. They may also follow tractors and lawnmowers.

Cattle Egrets usually first breed at 2 to 3 years of age. The male establishes a pairing territory in or near the colony and displays there to attract a mate. Displays include stretching the neck and raising plumes while swaying from side to side, making short flights with exaggerated deep wingbeats. The nest site is typically in a tree or shrub in a heron rookery on an island or in a swamp. The nest is built mainly by the female using materials collected mainly by the male. It is a platform or shallow bowl of sticks, often with green, leafy twigs added. The typically 3 to 4 (range 1 to 9) eggs are pale blue. Incubation is by both sexes for 21 to 26 days. Young are fed by both parents (by regurgitation). The young begin to climb around near the nest at around 15 to 20 days, to fly at 25 to 30 days, and become independent around 45 days.

Cattle Egrets are strongly migratory. Birds from northern breeding areas in North America may winter to the West Indies, Middle America, and northern South America. In the United States, they are common year-round in Florida, along the Gulf Coast, and in parts of the Southwest. Young birds may disperse great distances, even thousands of kilometers.

(Crosby 1972; Maddock and Geering 1994; Kaufman 1996; AOU 1998; Dunn and Alderfer 2011)

- American Ornithologists' Union. 1998. Check-list of North American Birds, 7th edition. American Ornithologists' Union, Washington, D.C.

- Crosby, G.T. 1972. Spread of the Cattle Egret in the Western Hemisphere. Bird-Banding. 43: 205-212.

- Dunn, J.L. and J. Alderfer. 2011. National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America. National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C.

- Kaufman, K. 1996. Lives of North American Birds. Houghton Mifflin, Boston

- Maddock, M. and D. Geering. 1994. Range expansion and migration of the Cattle Egret. Ostrich 65: 191-203.

Trusted

Comprehensive Description

Summary

"A stocky white bird often seen in grasslands and paddy fields,

accompanying cattle and other large mammals, catching insects and other

small vertebrates disturbed by these animals. During the breeding season

it aquires orange - buff coloured plumes on the back, crown and crown."

Trusted

Distribution

The cattle egret, due to its great range expansion in association

with cattle ranching, has become a true 'cosmopolitan' species. It

occurs in North America, generally not in the west or far north; and

Eurasia, though usually not in the east. It also inhabits Africa,

Australia and parts of South America. Cattle egret are native to Africa

and southern Spain. (Hancock and Elliott, 1978)

Biogeographic Regions: nearctic (Introduced ); palearctic (Introduced , Native ); oriental (Introduced ); ethiopian (Introduced , Native ); neotropical (Introduced ); australian (Introduced ); oceanic islands (Introduced )

Other Geographic Terms: cosmopolitan

Biogeographic Regions: nearctic (Introduced ); palearctic (Introduced , Native ); oriental (Introduced ); ethiopian (Introduced , Native ); neotropical (Introduced ); australian (Introduced ); oceanic islands (Introduced )

Other Geographic Terms: cosmopolitan

Trusted

National Distribution

Canada

Origin: NativeRegularity: Regularly occurring

Currently: Present

Confidence: Confident

Type of Residency: Breeding

United States

Origin: NativeRegularity: Regularly occurring

Currently: Present

Confidence: Confident

Type of Residency: Year-round

Trusted

Global Range: (>2,500,000 square km (greater than

1,000,000 square miles)) BREEDS: in Western Hemisphere locally from

California, southern Idaho, Colorado, North Dakota, southern

Saskatchewan, Minnesota, Wisconsin, southern Ontario, northern Ohio, and

Maine south, primarily in coastal lowlands, through Middle America and

West Indies to South America (northern Chile, northern Argentina,

southeastern Brazil). Breeding range is expanding with deforestation in

Central America. NORTHERN WINTER: throughout much of breeding range,

north to the southern U.S. In the U.S., most abundant in winter in

Florida, around the Salton Sea (California), on the coastal plains of

southern Texas, and around the mouth of the Mississippi River in

Louisiana (Root 1988). Introduced in Hawaii. Old World species that has

spread from populations introduced in South America (NGS 1983); some

have concluded that the species colonized South America on its own.

Trusted

Range

W Palearctic, Africa, North and South America.

- Clements, J. F., T. S. Schulenberg, M. J. Iliff, D. Roberson, T. A. Fredericks, B. L. Sullivan, and C. L. Wood. 2014. The eBird/Clements checklist of birds of the world: Version 6.9. Downloaded from http://www.birds.cornell.edu/clementschecklist/download/

Trusted

Physical Description

Morphology

The cattle egret is a medium sized bird, with a 'hunched' posture,

even when it is standing erect. In comparison to other egrets, it is

short-legged and thick-necked. The total length of the bird ranges from

46-56 cm, and its wingspan averages 88-96 cm. The basic plumage of the

adult of both sexes is pure white, with a dull orange or yellow bill,

and dull orange legs. For a brief period of time during the breeding

season, however, the plumage of the breeding adults is buffy at the

head, neck and back, and the eyes, legs and bill are a vivid red.

Because of this coloration, it is sometimes called the Buff-Backed

Heron. (Telfair, 1994; Hancock and Elliott, 1978; http://www.coos.or.us/~aigrette/ce.htm; http://www.mbr.nbs.gov/id/htmid/h2001id.html)

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; bilateral symmetry

Average mass: 220 g.

Other Physical Features: endothermic ; bilateral symmetry

Average mass: 220 g.

Trusted

"A snow-white lanky bird, very similar in non-breeding plumage to the

Little Egret, but recognisable by the colour of its bill which is yellow

not black. In the breeding season it acquires delicate golden-buff

hair-like plumes on head, neck and back. Sexes alike."

Trusted

Size

Cattle egrets generally attain a length of 46-56 cm, a wingspan of 88-96 cm, and a weight of around 360 g (Scott, 1987).

- Bryan J.C., Miller S.J., Yates C.S. and M. Minno. 2003. Variation in size and location of wading bird colonies in the Upper St. Johns River Basin, Florida, USA. Waterbirds 26:239-251.

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology. 2003. All About Birds species page: Bubulcus Ibis. Available online.

- Council for Agricultural Science and Technology (CAST). 2002. Invasive pest species impacts on agricultural production, natural resources, and the environment. Issue Paper 20. 18 p.

- Dugger B.D., Melvin S.L., and R.S. Finger. 2005. Abundance and community composition of waterbirds using the channelized Kissimmee River Floodplain, Fl. Southeastern Naturalist 4:435-446.

- Hancock, J. and H. Elliot.1978. The herons of the world. Harper and Row Publishing, New York. 304 p.

- Hilty S.L. and W.L. Brown. 1986. A guide to the girds of Colombia. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ. 836 p.

- Ivory, A. 2000. "Bubulcus ibis" (Online), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed July 16, 2007. Available online.

- Kaufman K. 1996. Lives of North American birds. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston. 675 pp.

- Maxwell G.R., II and H.W. Kale, II. 1977. Breeding biology of five species of herons in coastal Florida. Auk 94: 689-700.

- McKilligan N.G. 1990. Promiscuity in the cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis). Auk:107:134-341.

- Peterson R.T. 1980. A field guide to the birds. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston. 384 p.

- Scott S.L. 1987. Field guide to the birds of North America. National Geographic Society. Washington, D.C. 464 p.

- Telfair R.C. II. 1994. Cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis). In: The birds of North America, No. 113 (A. Poole and F. Gill, Eds.). The Academy of Natural Sciences, Washington, D.C.

- Weber W.J. 1972. A new world for the cattle egret. Natural History 81:56-63.

- Weber W.J. 1975. Notes on cattle egret breeding. Auk 92:111-117.

- Wetmore A. 1965. The birds of the Republic of Panama. Part I. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections vol. 150. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 483 p.

Trusted

Diagnostic Description

SubSpecies Varieties Races

"B. i. ibis (Linnaeus, 1758) B. i. coromandus (Boddaert, 1783) B. i. seychellarum (Salomonsen, 1934)"

Trusted

Look Alikes

Another common Florida egret, the snowy egret (Egretta thula),

is somewhat similar in appearance, but it is taller and the bill and

legs are black in adult specimens. The legs and the wingspan of snowy

egrets are also longer than those of B. ibis (Peterson 1980, Hilty and Brown 1986).

- Bryan J.C., Miller S.J., Yates C.S. and M. Minno. 2003. Variation in size and location of wading bird colonies in the Upper St. Johns River Basin, Florida, USA. Waterbirds 26:239-251.

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology. 2003. All About Birds species page: Bubulcus Ibis. Available online.

- Council for Agricultural Science and Technology (CAST). 2002. Invasive pest species impacts on agricultural production, natural resources, and the environment. Issue Paper 20. 18 p.

- Dugger B.D., Melvin S.L., and R.S. Finger. 2005. Abundance and community composition of waterbirds using the channelized Kissimmee River Floodplain, Fl. Southeastern Naturalist 4:435-446.

- Hancock, J. and H. Elliot.1978. The herons of the world. Harper and Row Publishing, New York. 304 p.

- Hilty S.L. and W.L. Brown. 1986. A guide to the girds of Colombia. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ. 836 p.

- Ivory, A. 2000. "Bubulcus ibis" (Online), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed July 16, 2007. Available online.

- Kaufman K. 1996. Lives of North American birds. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston. 675 pp.

- Maxwell G.R., II and H.W. Kale, II. 1977. Breeding biology of five species of herons in coastal Florida. Auk 94: 689-700.

- McKilligan N.G. 1990. Promiscuity in the cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis). Auk:107:134-341.

- Peterson R.T. 1980. A field guide to the birds. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston. 384 p.

- Scott S.L. 1987. Field guide to the birds of North America. National Geographic Society. Washington, D.C. 464 p.

- Telfair R.C. II. 1994. Cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis). In: The birds of North America, No. 113 (A. Poole and F. Gill, Eds.). The Academy of Natural Sciences, Washington, D.C.

- Weber W.J. 1972. A new world for the cattle egret. Natural History 81:56-63.

- Weber W.J. 1975. Notes on cattle egret breeding. Auk 92:111-117.

- Wetmore A. 1965. The birds of the Republic of Panama. Part I. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections vol. 150. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 483 p.

Trusted

Ecology

Habitat

The cattle egret is the most terrestrial heron, being well-adapted to

many diverse terrestrial and aquatic habitats. Though it does not

depend on aquatic habitats to survive, it does make frequent use of

them, even when they are not close to livestock-grazing areas. It is

also well-adapted to urban areas. In its breeding range, which is

similar to its winter range, it often nests in heronries established by

native ardeids. (Telfair, 1994)

Terrestrial Biomes: savanna or grassland ; forest ; rainforest ; scrub forest

Terrestrial Biomes: savanna or grassland ; forest ; rainforest ; scrub forest

Trusted

Habitat and Ecology

Habitat and Ecology

Systems

Behaviour

Most populations of this species are partially migratory, making

long-distance dispersive movements related to food resources in

connection with seasonal rainfall (del Hoyo et al. 1992). Other populations (e.g. in north-east Asia and North America) are fully migratory (del Hoyo et al. 1992, Snow and Perrins 1998). The species breeds throughout the year in the tropics with different regional peaks (del Hoyo et al.

1992) depending on food availability (Kushlan and Hancock 2005). It

breeds colonially, often with other species, in groups that number from a

few dozen to several thousand pairs, even up to 10,000 pairs in Africa

(del Hoyo et al. 1992). The nesting effort of the species is

related to rainfall patterns, leading to an annual variation in

productivity (Kushlan and Hancock 2005). Outside of the breeding season

the species remains gregarious (Brown et al. 1982, del Hoyo et al. 1992), feeding in loose flocks of 10-20 individuals (Brown et al. 1982) and often gathering in flocks of hundreds or even thousands of individuals where food is abundant (del Hoyo et al. 1992). Nocturnal roosting sites in Africa commonly hold a few hundred to 2,000 individuals (Brown et al. 1982). The species is a diurnal feeder (del Hoyo et al.

1992) and commonly associates with native grazing mammals or

domesticated livestock (Kushlan and Hancock 2005) and may follow farm

machinery to capture disturbed prey (del Hoyo et al. 1992). Habitat The species inhabits open grassy areas such as meadows (del Hoyo et al. 1992), livestock pastures (Kushlan and Hancock 2005), semi-arid steppe (del Hoyo et al. 1992) and open savanna grassland subject to seasonal inundation (Kushlan and Hancock 2005), dry arable fields (del Hoyo et al.

1992), artificial grassland sites (e.g. lawns, parks, road margins and

sports fields) (Kushlan and Hancock 2005), flood-plains (Hancock and

Kushlan 1984), freshwater swamps, rice-fields, wet pastures (del Hoyo et al.

1992), shallow marshes (Kushlan and Hancock 2005), mangroves (Hancock

and Kushlan 1984) and irrigated grasslands (with ponds, small

impoundments, wells, canals, small rivers and streams) (Kushlan and

Hancock 2005). It rarely occupies marine habitats or forested areas (del

Hoyo et al. 1992) although in Australia it may enter woodlands

and forests, and it shows a preference for freshwater (Marchant and

Higgins 1990) although it may also use brackish or saline habitats

(Kushlan and Hancock 2005). It occurs from sea-level up to c.1,500 m

(Kushlan and Hancock 2005) or locally up to c.4,000 m (Peru) (del Hoyo et al. 1992). Diet Its diet consists primarily of insects such as locusts, grasshoppers (del Hoyo et al. 1992), beetles, adult and larval Lepidoptera, Hemiptera, dragonflies (Hancock and Kushlan 1984) and centipedes but worms (Brown et al.

1982), spiders (Hancock and Kushlan 1984), crustaceans, frogs,

tadpoles, molluscs, fish, lizards, small birds, rodents and vegetable

matter (e.g. palm-nut pulp) may also be taken (del Hoyo et al. 1992). Breeding site

The nest is constructed of twigs and vegetation (Kushlan and Hancock

2005) and is positioned up to 20 m high in reedbeds (del Hoyo et al. 1992, Kushlan and Hancock 2005), marshes, mangroves, dense thickets (Kushlan and Hancock 2005), bushes or trees (del Hoyo et al.

1992, Kushlan and Hancock 2005), usually over or surrounded by water

(Kushlan and Hancock 2005). The species nests colonially in single- or

mixed-species groups with the nests placed close or touching (Snow and

Perrins 1998). Management information The species can

adversely affect the trees and bushes it uses for nesting, which may

lead to the abandonment of the colony site if it is not managed (Kushlan

and Hancock 2005).

Systems

- Terrestrial

- Freshwater

Trusted

Comments: Wet pastureland and marshes, fresh water

and brackish situations, dry fields, agricultural areas (especially

irrigated ones), garbage dumps. In West Indies, roosts at night in

mangrove swamps or on mangrove islands (Raffaele 1983). Nests in trees

on islands in lakes; along watercourses; in swamps; on mangrove cays;

near marshes. Usually nests with other herons or in single species

colonies.

Trusted

General Habitat

Gregarious. Usually attending grazing cattle. Not necessarily near water.

Trusted

Migration

Non-Migrant: Yes. At least some populations of this

species do not make significant seasonal migrations. Juvenile dispersal

is not considered a migration.

Locally Migrant: Yes. At least some populations of this species make local extended movements (generally less than 200 km) at particular times of the year (e.g., to breeding or wintering grounds, to hibernation sites).

Locally Migrant: Yes. At least some populations of this species make annual migrations of over 200 km.

Northern populations in North America are migratory; move north February to April or later, migrate south September into November. Extensive post-breeding dispersal in all compass directions July to early September in north (Palmer 1962).

Locally Migrant: Yes. At least some populations of this species make local extended movements (generally less than 200 km) at particular times of the year (e.g., to breeding or wintering grounds, to hibernation sites).

Locally Migrant: Yes. At least some populations of this species make annual migrations of over 200 km.

Northern populations in North America are migratory; move north February to April or later, migrate south September into November. Extensive post-breeding dispersal in all compass directions July to early September in north (Palmer 1962).

Trusted

Trophic Strategy

It has been calculated that an individual cattle egret can obtain up

to 50% more food and use only two-thirds as much energy catching it by

associating with cattle, as well as with other large ungulate species.

Thus it is a very opportunistic and non-competitive feeder. It commonly

associates with livestock, wild buffalo, rhino, elephant, hippo, zebra,

giraffe, eland, and waterbuck. Due to their practice of perching on

these animals' backs, cattle egrets are often grouped incorrectly with

'tick-birds.' In Australia, they have also been observed to associate

with horses, pigs, sheep, fowls, geese, and kangaroos. In the Carribean

they even follow the plough, capturing exposed earthworms. The cattle

egret's major prey is active insects which are disturbed by the grazing

activities of the cattle egret's host animals. It eats mostly

grasshoppers, crickets, spiders, flies, frogs, and noctuid moths. It is

a very active forager, usually feeding in loose aggregations of small

or large flocks of mixed sex and age, varying from tens to hundreds of

individuals. It may forage in smaller groups or singly. When feeding,

it usually walks in a steady strut, followed by a short dart forward,

and a quick stab. If they prey animal is small, it is immediately

swallowed. If it is larger, it may be jabbed or dipped in water a few

times, but it is not dismembered. (Telfair, 1994; Hancock and Elliott,

1992)

Trusted

Comments: Eats mainly insects and amphibians, also

reptiles and small rodents; usually feeds on dry or moist ground near

cattle or horses, away from water (Terres 1980), sometimes near farm

machinery.

Trusted

The common name of the cattle egret comes from their familiar habit of

foraging in pasturelands in association with livestock animals whose

movements and grazing activities flush out insect and other potential

prey items. Cattle egrets will also follow tractors in order to feed on

the organisms that are scared up (Scott 1987, Kaufman 1996). Crickets,

grasshoppers, beetles, moths, flies, and other small invertebrates and

vertebrates make up the bulk of the diet. Bubulcus ibis

is an opportunistic forager; it will eat parasites off of the bodies of

the livestock with which they coexist and can also consume relatively

large prey items like crayfish, fish, frogs, small snakes, and even bird

eggs and nestling birds. In urbanized settings cattle egrets will

scavenge trash heaps for edible material (Kaufman, 1996).

- Bryan J.C., Miller S.J., Yates C.S. and M. Minno. 2003. Variation in size and location of wading bird colonies in the Upper St. Johns River Basin, Florida, USA. Waterbirds 26:239-251.

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology. 2003. All About Birds species page: Bubulcus Ibis. Available online.

- Council for Agricultural Science and Technology (CAST). 2002. Invasive pest species impacts on agricultural production, natural resources, and the environment. Issue Paper 20. 18 p.

- Dugger B.D., Melvin S.L., and R.S. Finger. 2005. Abundance and community composition of waterbirds using the channelized Kissimmee River Floodplain, Fl. Southeastern Naturalist 4:435-446.

- Hancock, J. and H. Elliot.1978. The herons of the world. Harper and Row Publishing, New York. 304 p.

- Hilty S.L. and W.L. Brown. 1986. A guide to the girds of Colombia. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ. 836 p.

- Ivory, A. 2000. "Bubulcus ibis" (Online), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed July 16, 2007. Available online.

- Kaufman K. 1996. Lives of North American birds. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston. 675 pp.

- Maxwell G.R., II and H.W. Kale, II. 1977. Breeding biology of five species of herons in coastal Florida. Auk 94: 689-700.

- McKilligan N.G. 1990. Promiscuity in the cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis). Auk:107:134-341.

- Peterson R.T. 1980. A field guide to the birds. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston. 384 p.

- Scott S.L. 1987. Field guide to the birds of North America. National Geographic Society. Washington, D.C. 464 p.

- Telfair R.C. II. 1994. Cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis). In: The birds of North America, No. 113 (A. Poole and F. Gill, Eds.). The Academy of Natural Sciences, Washington, D.C.

- Weber W.J. 1972. A new world for the cattle egret. Natural History 81:56-63.

- Weber W.J. 1975. Notes on cattle egret breeding. Auk 92:111-117.

- Wetmore A. 1965. The birds of the Republic of Panama. Part I. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections vol. 150. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 483 p.

Trusted

Associations

In the African portion of their native range, cattle egrets co-occur

with elephants, rhinoceros, hippopotamus, and other large herbivores,

and across much of their non-native range they associate primarily with

cattle (Telfair 1994, Ivory 2000).Invasion History: Cattle egrets are

notable among exotic species in that they are one of the very few cases

in which initial expansion into historically non-native areas appears to

be a largely natural occurrence unassisted by humans (Weber, 1972). The

species is highly migratory and is capable of dispersing in seemingly

random directions across thousands of kilometers in a few days (Kaufman

1996, CAST 2002).Although the initial entry of Bubulcus ibis

into New World appears to have not relied on the helping hand of man,

current range expansion within the U.S. is related to extensive

landscape conversion to pasturelands (Telfair 1994).The first appearance

of B. ibis in the

New World dates to the late 1870s and 1880s from Suriname in

northeastern South America. By 1917, they had appeared in Colombia,

although they were not reported from Panama until 1954. B. ibis

apparently arrived in Florida in the 1940s and had begun establishing

breeding populations in the state in the 1950s (Wetmore 1965, Hilty and

Brown 1986). The animal is now abundant year-round throughout Florida.

Potential to Compete With Natives: Bubulcus ibis

is highly adaptable and capable of living in a number of human-altered

agricultural and urbanized environments. Although the potential exists

for them to out-compete co-occurring native species for nesting areas

and food resources, published findings suggest there has been little

impact of B. ibis

on native species in the U.S. (Weber 1972, Kauffman 1996). Cattle egrets

often occur as part of mixed-species nesting assemblages, and Maxwell

and Kale (1977) note that peak nesting in cattle egrets occurs after

that of most native herons. Dietary niche overlap is probably also

minimal as the diet of cattle egrets consists primarily of insects and

terrestrial invertebrates whereas other herons consume mostly primarily

fish and aquatic invertebrates (Weber 1972). Possible Economic

Consequences of Invasion: The negetive economic impacts of cattle egrets

in the IRL region and in Florida in general is likely to be minimal.

- Bryan J.C., Miller S.J., Yates C.S. and M. Minno. 2003. Variation in size and location of wading bird colonies in the Upper St. Johns River Basin, Florida, USA. Waterbirds 26:239-251.

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology. 2003. All About Birds species page: Bubulcus Ibis. Available online.

- Council for Agricultural Science and Technology (CAST). 2002. Invasive pest species impacts on agricultural production, natural resources, and the environment. Issue Paper 20. 18 p.

- Dugger B.D., Melvin S.L., and R.S. Finger. 2005. Abundance and community composition of waterbirds using the channelized Kissimmee River Floodplain, Fl. Southeastern Naturalist 4:435-446.

- Hancock, J. and H. Elliot.1978. The herons of the world. Harper and Row Publishing, New York. 304 p.

- Hilty S.L. and W.L. Brown. 1986. A guide to the girds of Colombia. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ. 836 p.

- Ivory, A. 2000. "Bubulcus ibis" (Online), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed July 16, 2007. Available online.

- Kaufman K. 1996. Lives of North American birds. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston. 675 pp.

- Maxwell G.R., II and H.W. Kale, II. 1977. Breeding biology of five species of herons in coastal Florida. Auk 94: 689-700.

- McKilligan N.G. 1990. Promiscuity in the cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis). Auk:107:134-341.

- Peterson R.T. 1980. A field guide to the birds. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston. 384 p.

- Scott S.L. 1987. Field guide to the birds of North America. National Geographic Society. Washington, D.C. 464 p.

- Telfair R.C. II. 1994. Cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis). In: The birds of North America, No. 113 (A. Poole and F. Gill, Eds.). The Academy of Natural Sciences, Washington, D.C.

- Weber W.J. 1972. A new world for the cattle egret. Natural History 81:56-63.

- Weber W.J. 1975. Notes on cattle egret breeding. Auk 92:111-117.

- Wetmore A. 1965. The birds of the Republic of Panama. Part I. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections vol. 150. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 483 p.

Trusted

Population Biology

Number of Occurrences

Note: For many non-migratory species, occurrences are roughly equivalent to populations.

Estimated Number of Occurrences: > 300

Estimated Number of Occurrences: > 300

Trusted

Global Abundance

>1,000,000 individuals

Comments: Most of coastal U.S. breeding population is on the Florida coast (250,000 birds) and Gulf Coast (170,000); 20,000 breeders on the Atlantic coast north of Florida. Preceding population figures do not include birds breeding in inland sites (e.g., 242,000 in Texas in 1979). Breeding populations often vary greatly in successive years.

Comments: Most of coastal U.S. breeding population is on the Florida coast (250,000 birds) and Gulf Coast (170,000); 20,000 breeders on the Atlantic coast north of Florida. Preceding population figures do not include birds breeding in inland sites (e.g., 242,000 in Texas in 1979). Breeding populations often vary greatly in successive years.

Trusted

Cattle egrets are abundant throughout Florida. Bryan et al (2003) reports that Bubulcus ibis

was the most common nesting species in nesting bird colony surveys

conducted in the Upper St. Johns River basin in 1993-1995 and 1998-2000.

Similarly, Dugger et al (2005) confirmed that that B. ibis

was the most abundant waterbird utilizing the channelized Kissimmee

River in the wet season during surveys conducted between 1996 and 1998.

This information confirms the ability of B. ibis to effectively utilize urbanized or otherwise altered habitats.

- Bryan J.C., Miller S.J., Yates C.S. and M. Minno. 2003. Variation in size and location of wading bird colonies in the Upper St. Johns River Basin, Florida, USA. Waterbirds 26:239-251.

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology. 2003. All About Birds species page: Bubulcus Ibis. Available online.

- Council for Agricultural Science and Technology (CAST). 2002. Invasive pest species impacts on agricultural production, natural resources, and the environment. Issue Paper 20. 18 p.

- Dugger B.D., Melvin S.L., and R.S. Finger. 2005. Abundance and community composition of waterbirds using the channelized Kissimmee River Floodplain, Fl. Southeastern Naturalist 4:435-446.

- Hancock, J. and H. Elliot.1978. The herons of the world. Harper and Row Publishing, New York. 304 p.

- Hilty S.L. and W.L. Brown. 1986. A guide to the girds of Colombia. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ. 836 p.

- Ivory, A. 2000. "Bubulcus ibis" (Online), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed July 16, 2007. Available online.

- Kaufman K. 1996. Lives of North American birds. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston. 675 pp.

- Maxwell G.R., II and H.W. Kale, II. 1977. Breeding biology of five species of herons in coastal Florida. Auk 94: 689-700.

- McKilligan N.G. 1990. Promiscuity in the cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis). Auk:107:134-341.

- Peterson R.T. 1980. A field guide to the birds. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston. 384 p.

- Scott S.L. 1987. Field guide to the birds of North America. National Geographic Society. Washington, D.C. 464 p.

- Telfair R.C. II. 1994. Cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis). In: The birds of North America, No. 113 (A. Poole and F. Gill, Eds.). The Academy of Natural Sciences, Washington, D.C.

- Weber W.J. 1972. A new world for the cattle egret. Natural History 81:56-63.

- Weber W.J. 1975. Notes on cattle egret breeding. Auk 92:111-117.

- Wetmore A. 1965. The birds of the Republic of Panama. Part I. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections vol. 150. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 483 p.

Trusted

General Ecology

Life History and Behavior

Behavior

Behaviour

"The Cattle Egret is less dependent on the neighbourhood of water than

are most of its family. It is met with gregariously on grass- and

pasture-land both on the margins of tanks and jheels as well as further

inland. The birds are in constant attendance on grazing cattle, stalking

alongside the animals, running in and out between their legs, or riding

on their backs for a change. They keep an unceasing look-out for the

grasshoppers and other insects disturbed in the animals' progress

through the grass, darting out their long flexible necks and pointed

bills and snapping them up as soon as they show any movement. They also

pick off blood-sucking flies, ticks and other parasitic insects from the

backs and bellies of the oxen and buffaloes, jumping up for them as

they scurry alongside or alighting complacently on the animals' heads

and backs to reach the less accessible parts. Their staple food, unlike

that of their marsh-haunting cousins, is insects, but they do not

despise frogs and lizards whenever available. Flies—both the House-Fly

and the Blue-bottle-—are greatly relished. The birds are as a rule tame,

running or stalking about fearlessly amongst the cattle within a few

feet of the observer, and completely engrossed in the search for food.

Cattle Egrets have regular roosts in favourite trees to which they

resort every evening, flying more or less in a disorderly rabble, with

neck folded back, head hunched in between the shoulders, legs tucked

under the tail and projecting behind like a rudder."

Trusted

Life Expectancy

Range lifespan

Status: wild: 23 (high) years.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 204 months.

Status: wild: 23 (high) years.

Average lifespan

Status: wild: 204 months.

Trusted

Lifespan, longevity, and ageing

Maximum longevity: 23 years (wild) Observations: In Hawaii, reported to

breed twice a year and year round (http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/).

Trusted

Reproduction

The cattle egret is seasonally monogamous. It pair-bonds, but at the

start of the breeding season there can be a temporary group of 1 male

and 2 females. Breeding starts when small groups of males establish

territories. Soon after this, aggression increases, and they begin to

perform various elaborate courtship displays, attracting groups of

females. Immediately before pairing, a female will attempt to subdue

the displaying male by landing on his back. Eventually, the male will

allow one female to remain in his territory, and within a few hours, the

pair-bond is secure. The female then follows the male to another site

where the nest will be built. Copulation usually also takes place at

this second site. There is little display involved with copulation.

Some rapes and rape attempts have been documented. (Telfair, 1994)

Cattle egrets nest is large colonies with other wading birds. Pairs sometimes reuse old nests, or build new ones with live or dead vegetation. They will build in any place that can support a nest. Both sexes participate in nest-building: the female usually builds with materials brought by the male. They often steal sticks and other materials from neighbors' unattended nests. Material is continuously added to the bulky nests during incubation and after hatching. Throughout mating, nesting, and incubation, a Greeting Ceremony is given whenever one mate returns to the nest to join the other. The Greeting Ceremony involves erection of the back plumes, and flattening of the crest feathers. Eggs are laid every 2 days, and the female does not become attentive to the nest until the last egg is laid. The eggs are light sky blue, turning lighter as time passes. Clutch size is usually 3-4 eggs, although extremes of 1 and 9 have been recorded. Incubation is carried out by both sexes, and lasts 24 days. During the first week, nestlings are easily overheated, and so the parents shade them from the sun beneath their wings. Both parents brood constantly for the first 10 days. The parents may accept chicks from other broods only if they are less than 14 days old. Begging for food becomes very aggressive in days 4-8, and the nestlings are very competative with one another. Siblicide is uncommon, though sibling aggression is strong. Most of the chicks' growth is completed in the nest, but by 14-21 days, the chicks are capable of leaving the nest and climbing in vegetation, and are thus referred to as 'branchers.' At this stage, they remain nearby and continue to beg for food. At 45 days, they are independent, at 50 days they can make short flights, and at around 60 days, they fly to foraging areas. (Telfair, 1994; http://www.coos.or.us/~aigrette/ce.htm)

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; oviparous

Average time to hatching: 22 days.

Average eggs per season: 3.

Cattle egrets nest is large colonies with other wading birds. Pairs sometimes reuse old nests, or build new ones with live or dead vegetation. They will build in any place that can support a nest. Both sexes participate in nest-building: the female usually builds with materials brought by the male. They often steal sticks and other materials from neighbors' unattended nests. Material is continuously added to the bulky nests during incubation and after hatching. Throughout mating, nesting, and incubation, a Greeting Ceremony is given whenever one mate returns to the nest to join the other. The Greeting Ceremony involves erection of the back plumes, and flattening of the crest feathers. Eggs are laid every 2 days, and the female does not become attentive to the nest until the last egg is laid. The eggs are light sky blue, turning lighter as time passes. Clutch size is usually 3-4 eggs, although extremes of 1 and 9 have been recorded. Incubation is carried out by both sexes, and lasts 24 days. During the first week, nestlings are easily overheated, and so the parents shade them from the sun beneath their wings. Both parents brood constantly for the first 10 days. The parents may accept chicks from other broods only if they are less than 14 days old. Begging for food becomes very aggressive in days 4-8, and the nestlings are very competative with one another. Siblicide is uncommon, though sibling aggression is strong. Most of the chicks' growth is completed in the nest, but by 14-21 days, the chicks are capable of leaving the nest and climbing in vegetation, and are thus referred to as 'branchers.' At this stage, they remain nearby and continue to beg for food. At 45 days, they are independent, at 50 days they can make short flights, and at around 60 days, they fly to foraging areas. (Telfair, 1994; http://www.coos.or.us/~aigrette/ce.htm)

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; oviparous

Average time to hatching: 22 days.

Average eggs per season: 3.

Trusted

Clutch size is 2-6 (commonly 3-4). Incubation, by both sexes, lasts

21-24 days. Young can fly short distances at 40 days, reasonably well at

50 days. May breed at 1 year. Usually nests in colonies.

Trusted

"The season, depending on the monsoons, is mainly June to August in N.

India ; November /December in the south. The birds breed in colonies

usually in company with PaddyBirds and sometimes also with Darters,

cormorants and herons. The nest is of the usual crow pattern—an untidy

structure of twigs. It is built in trees not necessarily near water and

often in the midst of a noisy bazaar in a town or village. Three to 5

eggs form the normal clutch. They are a pale skim-milk blue in colour."

Trusted

Cattle egret breeding season in central Florida extends from mid April

through July (Weber 1972). Individuals enter the breeding population at

2-3 years of age (Kaufman 1996).Cattle egrets are colonial breeders that

are often found alongside other species of herons and egrets in

mixed-colony shoreline breeding assemblages. Males establish breeding

territories and courtship involves elaborate male displays. Once pairs

have been established females construct nests utilizing material

provided mainly by the males. Nest building and breeding is usually

completed in three days, after which the birds begin to lose their

breeding colors (Weber 1972, Kaufman 1996).There is a degree of

promiscuity in the species, with males frequently mating with more than

one female during the breeding season (McKilligan 1990).

- Bryan J.C., Miller S.J., Yates C.S. and M. Minno. 2003. Variation in size and location of wading bird colonies in the Upper St. Johns River Basin, Florida, USA. Waterbirds 26:239-251.

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology. 2003. All About Birds species page: Bubulcus Ibis. Available online.

- Council for Agricultural Science and Technology (CAST). 2002. Invasive pest species impacts on agricultural production, natural resources, and the environment. Issue Paper 20. 18 p.

- Dugger B.D., Melvin S.L., and R.S. Finger. 2005. Abundance and community composition of waterbirds using the channelized Kissimmee River Floodplain, Fl. Southeastern Naturalist 4:435-446.

- Hancock, J. and H. Elliot.1978. The herons of the world. Harper and Row Publishing, New York. 304 p.

- Hilty S.L. and W.L. Brown. 1986. A guide to the girds of Colombia. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ. 836 p.

- Ivory, A. 2000. "Bubulcus ibis" (Online), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed July 16, 2007. Available online.

- Kaufman K. 1996. Lives of North American birds. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston. 675 pp.

- Maxwell G.R., II and H.W. Kale, II. 1977. Breeding biology of five species of herons in coastal Florida. Auk 94: 689-700.

- McKilligan N.G. 1990. Promiscuity in the cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis). Auk:107:134-341.

- Peterson R.T. 1980. A field guide to the birds. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston. 384 p.

- Scott S.L. 1987. Field guide to the birds of North America. National Geographic Society. Washington, D.C. 464 p.

- Telfair R.C. II. 1994. Cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis). In: The birds of North America, No. 113 (A. Poole and F. Gill, Eds.). The Academy of Natural Sciences, Washington, D.C.

- Weber W.J. 1972. A new world for the cattle egret. Natural History 81:56-63.

- Weber W.J. 1975. Notes on cattle egret breeding. Auk 92:111-117.

- Wetmore A. 1965. The birds of the Republic of Panama. Part I. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections vol. 150. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 483 p.

Trusted

Growth

Mean clutch size of Bubulcus ibis

in Florida is approximately 3-4 eggs per nest, although clutch sizes

ranging from 1-9 eggs have been recorded (Weber 1972, Kaufman 1996). One

egg with a length of 4-5 cm is laid every other day during nesting, and

the eggs hatch sequentially, approximately 24 days after they are laid.

Survival retes of the earlier hatchlings is better than that of the

later hatchlings, and is related to food availability (Weber 1972,

1975). Fledglings begin to fly 25-30 days after hatching, and they

become independent around 45 days post-hatch (Kaufman, 1996).

- Bryan J.C., Miller S.J., Yates C.S. and M. Minno. 2003. Variation in size and location of wading bird colonies in the Upper St. Johns River Basin, Florida, USA. Waterbirds 26:239-251.

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology. 2003. All About Birds species page: Bubulcus Ibis. Available online.

- Council for Agricultural Science and Technology (CAST). 2002. Invasive pest species impacts on agricultural production, natural resources, and the environment. Issue Paper 20. 18 p.

- Dugger B.D., Melvin S.L., and R.S. Finger. 2005. Abundance and community composition of waterbirds using the channelized Kissimmee River Floodplain, Fl. Southeastern Naturalist 4:435-446.

- Hancock, J. and H. Elliot.1978. The herons of the world. Harper and Row Publishing, New York. 304 p.

- Hilty S.L. and W.L. Brown. 1986. A guide to the girds of Colombia. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ. 836 p.

- Ivory, A. 2000. "Bubulcus ibis" (Online), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed July 16, 2007. Available online.

- Kaufman K. 1996. Lives of North American birds. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston. 675 pp.

- Maxwell G.R., II and H.W. Kale, II. 1977. Breeding biology of five species of herons in coastal Florida. Auk 94: 689-700.

- McKilligan N.G. 1990. Promiscuity in the cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis). Auk:107:134-341.

- Peterson R.T. 1980. A field guide to the birds. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston. 384 p.

- Scott S.L. 1987. Field guide to the birds of North America. National Geographic Society. Washington, D.C. 464 p.

- Telfair R.C. II. 1994. Cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis). In: The birds of North America, No. 113 (A. Poole and F. Gill, Eds.). The Academy of Natural Sciences, Washington, D.C.

- Weber W.J. 1972. A new world for the cattle egret. Natural History 81:56-63.

- Weber W.J. 1975. Notes on cattle egret breeding. Auk 92:111-117.

- Wetmore A. 1965. The birds of the Republic of Panama. Part I. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections vol. 150. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 483 p.

Trusted

Molecular Biology and Genetics

Molecular Biology

Barcode data: Bubulcus ibis

The following is a representative barcode sequence, the centroid of all available sequences for this species.

There are 10 barcode sequences available from BOLD and GenBank.

Below is a sequence of the barcode region Cytochrome oxidase subunit 1 (COI or COX1) from a member of the species.

See the BOLD taxonomy browser for more complete information about this specimen and other sequences.

Download FASTA File

There are 10 barcode sequences available from BOLD and GenBank.

Below is a sequence of the barcode region Cytochrome oxidase subunit 1 (COI or COX1) from a member of the species.

See the BOLD taxonomy browser for more complete information about this specimen and other sequences.

NNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNCTTCGTAATAATCTTCTTCATAGTAATACCAATCATAATTGGAGGGTTCGGAAACTGACTAGTCCCACTCATAATTGGTGCTCCAGACATAGCATTCCCGCGCATAAATAACATAAGCTTCTGACTTCTACCACCATCATTTATACTCCTACTAGCCTCATCCACAGTTGAAGCAGGAGCAGGTACAGGTTGAACAGTCTACCCACCATTAGCCGGCAACCTAGCTCATGCCGGAGCCTCAGTAGACCTGGCCATCTTCTCCCTCCACCTAGCAGGTGTATCCTCCATCTTAGGGGCAATTAACTTCATCACAACTGCCATCAACATAAAACCCCCAGCCCTATCACAATACCAAACCCCCCTATTCGTATGATCCGTCCTAATTACCGCTGTCCTACTCCTACTCTCACTTCCAGTCCTTGCCGCAGGTATTACAATACTACTAACCGACCGAAACTTAAACACCACATTCTTCGACCCAGCCGGAGGTGGAGACCCAGTCCTCTATNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNNN

-- end --

-- end --

Download FASTA File

Trusted

Statistics of barcoding coverage: Bubulcus ibis

Barcode of Life Data Systems (BOLDS) Stats

Public Records: 16

Specimens with Barcodes: 26

Species With Barcodes: 1

Public Records: 16

Specimens with Barcodes: 26

Species With Barcodes: 1

Trusted

Conservation

Conservation Status

The cattle egret is the most plentiful ardeid in many areas of the

U.S. Its range continues to expand as a result of widespread landscape

conversion to pasturelands, where these birds forage with cattle.

(Telfair, 1994)

US Migratory Bird Act: protected

US Federal List: no special status

CITES: no special status

State of Michigan List: no special status

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: least concern

US Migratory Bird Act: protected

US Federal List: no special status

CITES: no special status

State of Michigan List: no special status

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: least concern

Trusted

IUCN Red List Assessment

Red List Category

LC

Least Concern

Red List Criteria

Version

3.1

Year Assessed

2014

Assessor/s

BirdLife International

Reviewer/s

Butchart, S.

Contributor/s

Justification

This

species has an extremely large range, and hence does not approach the

thresholds for Vulnerable under the range size criterion (Extent of

Occurrence <20,000 km2 combined with a declining or fluctuating range

size, habitat extent/quality, or population size and a small number of

locations or severe fragmentation). The population trend appears to be

increasing, and hence the species does not approach the thresholds for

Vulnerable under the population trend criterion (>30% decline over

ten years or three generations). The population size is extremely large,

and hence does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the

population size criterion (<10,000 mature individuals with a

continuing decline estimated to be >10% in ten years or three

generations, or with a specified population structure). For these

reasons the species is evaluated as Least Concern.

History

- 2012Least Concern

Trusted

National NatureServe Conservation Status

Canada

Rounded National Status Rank: N1B - Critically ImperiledUnited States

Rounded National Status Rank: N5B,N5N : N5B: Secure - Breeding, N5N: Secure - Nonbreeding

Trusted

Status in Egypt

Resident breeder, regular passage visitor and winter visitor.

Trusted

Trends

Population

Population

Population Trend

The population is estimated to number 3,800,000-7,600,000 individuals.

Population Trend

Increasing

Trusted

Global Long Term Trend: Increase of >25%

Comments: U.S. population increased greatly between the 1950s and early 1970s (Bock and Lepthien 1976). Breeding Bird Survey data indicate a significant population increase in North America between 1966 and 1989 (Droege and Sauer 1990). See Spendelow and Patton (1988) for further details.

Comments: U.S. population increased greatly between the 1950s and early 1970s (Bock and Lepthien 1976). Breeding Bird Survey data indicate a significant population increase in North America between 1966 and 1989 (Droege and Sauer 1990). See Spendelow and Patton (1988) for further details.

Trusted

Threats

Major Threats

Large colonies nesting

in urban areas are perceived as a public nuisance and may be persecuted

(e.g. by disturbance to prevent colony establishment, removal or direct

killing) (Kushlan and Hancock 2005). In its breeding range the species

is threatened by wetland degradation and destruction such as lake

drainage for irrigation and hydroelectric power production (Armenia)

(Balian et al. 2002), and in some parts of its range it is susceptible to pesticide poisoning (organophosphates and carbamates) (Kwon et al. 2004). Utilisation The species is hunted and traded at traditional medicine markets in Nigeria (Nikolaus 2001).

Trusted

Large colonies in urban areas are considered a nuiscance and are

persecuted. Habitat degradation and destruction. Pesticide poisoning

Trusted

Relevance to Humans and Ecosystems

Benefits

Cattle egrets may transmit parasites and other disease organisms to

livestock and people, but this is very speculative. Some heronries are

considered nuisances when near structures used by humans due to noise,

odor, concern over health hazards, and potential danger to aircraft.

(Telfair)

Trusted

Some ranchers rely on cattle egrets for fly control more than they do pesticides.

Trusted

Wikipedia

Cattle egret

The cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis) is a cosmopolitan species of heron (family Ardeidae) found in the tropics, subtropics and warm temperate zones. It is the only member of the monotypic genus Bubulcus, although some authorities regard its two subspecies as full species, the western cattle egret and the eastern cattle egret. Despite the similarities in plumage to the egrets of the genus Egretta, it is more closely related to the herons of Ardea. Originally native to parts of Asia, Africa and Europe, it has undergone a rapid expansion in its distribution and successfully colonised much of the rest of the world in the last century.

It is a white bird adorned with buff plumes in the breeding season. It nests in colonies, usually near bodies of water and often with other wading birds. The nest is a platform of sticks in trees or shrubs. Cattle egrets exploit drier and open habitats more than other heron species. Their feeding habitats include seasonally inundated grasslands, pastures, farmlands, wetlands and rice paddies. They often accompany cattle or other large mammals, catching insect and small vertebrate prey disturbed by these animals. Some populations of the cattle egret are migratory and others show post-breeding dispersal.

The adult cattle egret has few predators, but birds or mammals may raid its nests, and chicks may be lost to starvation, calcium deficiency or disturbance from other large birds. This species maintains a special relationship with cattle, which extends to other large grazing mammals; wider human farming is believed to be a major cause of their suddenly expanded range. The cattle egret removes ticks and flies from cattle and consumes them. This benefits both species, but it has been implicated in the spread of tick-borne animal diseases.

The cattle egret was first described in 1758 by Linnaeus in his Systema naturae as Ardea ibis,[2] but was moved to its current genus by Charles Lucien Bonaparte in 1855.[3] Its genus name Bubulcus is Latin for herdsman, referring, like the English name, to this species' association with cattle.[4] Ibis is a Latin and Greek word which originally referred to another white wading bird, the sacred ibis.[5]

The cattle egret has two geographical races which are sometimes classified as full species, the western cattle egret, B. ibis, and eastern cattle egret, B. coromandus. The two forms were split by McAllan and Bruce,[6] but were regarded as conspecific by almost all other recent authors until the publication of the influential Birds of South Asia.[7] The eastern subspecies B. (i.) coromandus, described by Pieter Boddaert in 1783, breeds in Asia and Australasia, and the western nominate form occupies the rest of the species range, including the Americas.[8] Some authorities recognise a third Seychelles subspecies, B. i. seychellarum, which was first described by Finn Salomonsen in 1934.[9]

Despite superficial similarities in appearance, the cattle egret is more closely related to the genus Ardea, which comprises the great or typical herons and the great egret (A. alba), than to the majority of species termed egrets in the genus Egretta.[10] Rare cases of hybridization with little blue herons Egretta caerulea, little egrets Egretta garzetta and snowy egrets Egretta thula have been recorded.[11]

B. i. coromandus differs from the nominate subspecies in breeding plumage, when the buff colour on its head extends to the cheeks and throat, and the plumes are more golden in colour. This subspecies' bill and tarsus are longer on average than in B. i. ibis.[15] B. i. seychellarum is smaller and shorter-winged than the other forms. It has white cheeks and throat, like B. i. ibis, but the nuptial plumes are golden, as with B. i. coromandus.[9]

The positioning of the egret's eyes allows for binocular vision during feeding,[16] and physiological studies suggest that the species may be capable of crepuscular or nocturnal activity.[17] Adapted to foraging on land, they have lost the ability possessed by their wetland relatives to accurately correct for light refraction by water.[18]

This species gives a quiet, throaty rick-rack call at the breeding colony, but is otherwise largely silent.[19]

The cattle egret has undergone one of the most rapid and wide reaching natural expansions of any bird species.[19] It was originally native to parts of Southern Spain and Portugal, tropical and subtropical Africa and humid tropical and subtropical Asia. In the end of the 19th century it began expanding its range into southern Africa, first breeding in the Cape Province in 1908.[20] Cattle egrets were first sighted in the Americas on the boundary of Guiana and Suriname in 1877, having apparently flown across the Atlantic Ocean.[8][12] It was not until the 1930s that the species is thought to have become established in that area.[21]

The cattle egret has undergone one of the most rapid and wide reaching natural expansions of any bird species.[19] It was originally native to parts of Southern Spain and Portugal, tropical and subtropical Africa and humid tropical and subtropical Asia. In the end of the 19th century it began expanding its range into southern Africa, first breeding in the Cape Province in 1908.[20] Cattle egrets were first sighted in the Americas on the boundary of Guiana and Suriname in 1877, having apparently flown across the Atlantic Ocean.[8][12] It was not until the 1930s that the species is thought to have become established in that area.[21]

The species first arrived in North America in 1941 (these early sightings were originally dismissed as escapees), bred in Florida in 1953, and spread rapidly, breeding for the first time in Canada in 1962.[20] It is now commonly seen as far west as California. It was first recorded breeding in Cuba in 1957, in Costa Rica in 1958, and in Mexico in 1963, although it was probably established before that.[21] In Europe, the species had historically declined in Spain and Portugal, but in the latter part of the 20th century it expanded back through the Iberian Peninsula, and then began to colonise other parts of Europe; southern France in 1958, northern France in 1981 and Italy in 1985.[20] Breeding in the United Kingdom was recorded for the first time in 2008 only a year after an influx seen in the previous year.[22][23] In 2008, cattle egrets were also reported as having moved into Ireland for the first time.[24]

In Australia, the colonisation began in the 1940s, with the species establishing itself in the north and east of the continent.[25] It began to regularly visit New Zealand in the 1960s. Since 1948 the cattle egret has been permanently resident in Israel. Prior to 1948 it was only a winter visitor.[26]

The massive and rapid expansion of the cattle egret's range is due to its relationship with humans and their domesticated animals. Originally adapted to a commensal relationship with large browsing animals, it was easily able to switch to domesticated cattle and horses. As the keeping of livestock spread throughout the world, the cattle egret was able to occupy otherwise empty niches.[27] Many populations of cattle egrets are highly migratory and dispersive,[19] and this has helped the species' range expansion. The species has been seen as a vagrant in various sub-Antarctic islands, including South Georgia, Marion Island, the South Sandwich Islands and the South Orkney Islands.[28] A small flock of eight birds was also seen in Fiji in 2008.[29]

In addition to the natural expansion of its range, cattle egrets have been deliberately introduced into a few areas. The species was introduced to Hawaii in 1959, and to the Chagos Archipelago in 1955. Successful releases were also made in the Seychelles and Rodrigues, but attempts to introduce the species to Mauritius failed. Numerous birds were also released by Whipsnade Zoo in England, but the species was never established.[30]

Although the cattle egret sometimes feeds in shallow water, unlike most herons it is typically found in fields and dry grassy habitats, reflecting its greater dietary reliance on terrestrial insects rather than aquatic prey.[31]

Some populations of cattle egrets are migratory, others are dispersive, and distinguishing between the two can be difficult for this species.[19] In many areas populations can be both sedentary

and migratory. In the northern hemisphere, migration is from cooler

climes to warmer areas, but cattle egrets nesting in Australia migrate

to cooler Tasmania and New Zealand in the winter and return in the spring.[25]

Migration in western Africa is in response to rainfall, and in South

America migrating birds travel south of their breeding range in the

non-breeding season.[19] Populations in southern India appear to show local migrations in response to the monsoons. They move north from Kerala after September.[32][33] During winter, many birds have been seen flying at night with flocks of Indian pond herons (Ardeola grayii) on the south-eastern coast of India[34] and a winter influx has also been noted in Sri Lanka.[7]

Some populations of cattle egrets are migratory, others are dispersive, and distinguishing between the two can be difficult for this species.[19] In many areas populations can be both sedentary

and migratory. In the northern hemisphere, migration is from cooler

climes to warmer areas, but cattle egrets nesting in Australia migrate

to cooler Tasmania and New Zealand in the winter and return in the spring.[25]

Migration in western Africa is in response to rainfall, and in South

America migrating birds travel south of their breeding range in the

non-breeding season.[19] Populations in southern India appear to show local migrations in response to the monsoons. They move north from Kerala after September.[32][33] During winter, many birds have been seen flying at night with flocks of Indian pond herons (Ardeola grayii) on the south-eastern coast of India[34] and a winter influx has also been noted in Sri Lanka.[7]

Young birds are known to disperse up to 5,000 km (3,100 mi) from their breeding area. Flocks may fly vast distances and have been seen over seas and oceans including in the middle of the Atlantic.[35]

The cattle egret nests in colonies, which are often, but not always, found around bodies of water.[19]

The colonies are usually found in woodlands near lakes or rivers, in

swamps, or on small inland or coastal islands, and are sometimes shared

with other wetland birds, such as herons, egrets, ibises and cormorants. The breeding season varies within South Asia.[7] Nesting in northern India begins with the onset of monsoons in May.[37] The breeding season in Australia is November to early January, with one brood laid per season.[38] The North American breeding season lasts from April to October.[19] In the Seychelles, the breeding season of the subspecies B.i. seychellarum is April to October.[39]

The cattle egret nests in colonies, which are often, but not always, found around bodies of water.[19]

The colonies are usually found in woodlands near lakes or rivers, in

swamps, or on small inland or coastal islands, and are sometimes shared

with other wetland birds, such as herons, egrets, ibises and cormorants. The breeding season varies within South Asia.[7] Nesting in northern India begins with the onset of monsoons in May.[37] The breeding season in Australia is November to early January, with one brood laid per season.[38] The North American breeding season lasts from April to October.[19] In the Seychelles, the breeding season of the subspecies B.i. seychellarum is April to October.[39]

The male displays in a tree in the colony, using a range of ritualised behaviours such as shaking a twig and sky-pointing (raising his bill vertically upwards),[40] and the pair forms over three or four days. A new mate is chosen in each season and when re-nesting following nest failure.[41] The nest is a small untidy platform of sticks in a tree or shrub constructed by both parents. Sticks are collected by the male and arranged by the female, and stick-stealing is rife.[14] The clutch size can be anywhere from one to five eggs, although three or four is most common. The pale bluish-white eggs are oval-shaped and measure 45 mm × 53 mm (1.8 in × 2.1 in).[38] Incubation lasts around 23 days, with both sexes sharing incubation duties.[19] The chicks are partly covered with down at hatching, but are not capable of fending for themselves; they become capable of regulating their temperature at 9–12 days and are fully feathered in 13–21 days.[42] They begin to leave the nest and climb around at 2 weeks, fledge at 30 days and become independent at around the 45th day.[41]

The cattle egret engages in low levels of brood parasitism, and there are a few instances of cattle egret eggs being laid in the nests of snowy egrets and little blue herons, although these eggs seldom hatch.[19] There is also evidence of low levels of intraspecific brood parasitism, with females laying eggs in the nests of other cattle egrets. As much as 30% extra-pair copulations have been noted.[43][44]

The dominant factor in nesting mortality is starvation. Sibling rivalry can be intense, and in South Africa third and fourth chicks inevitably starve.[41] In the dryer habitats with fewer amphibians the diet may lack sufficient vertebrate content and may cause bone abnormalities in growing chicks due to calcium deficiency.[45] In Barbados, nests were sometimes raided by vervet monkeys,[8] and a study in Florida reported the fish crow and black rat as other possible nest raiders. The same study attributed some nestling mortality to brown pelicans nesting in the vicinity, which accidentally, but frequently, dislodged nests or caused nestlings to fall.[46] In Australia, Torresian crows, wedge-tailed eagles and white-bellied sea eagles take eggs or young, and tick infestation and viral infections may also be causes of mortality.[14]

A cattle egret will weakly defend the area around a grazing animal against others of the same species, but if the area is swamped by egrets it will give up and continue foraging elsewhere. Where numerous large animals are present, cattle egrets selectively forage around species that move at around 5–15 steps per minute, avoiding faster and slower moving herds; in Africa, cattle egrets selectively forage behind plains zebras, waterbuck, blue wildebeest and Cape buffalo.[54] Dominant birds feed nearest to the host, and obtain more food.[14]

The cattle egret may also show versatility in its diet. On islands with seabird colonies, it will prey on the eggs and chicks of terns and other seabirds.[30] During migration it has also been reported to eat exhausted migrating landbirds.[55] Birds of the Seychelles race also indulge in some kleptoparasitism, chasing the chicks of sooty terns and forcing them to disgorge food.[56]

A conspicuous species, the cattle egret has attracted many common names.

These mostly relate to its habit of following cattle and other large

animals, and it is known variously as cow crane, cow bird or cow heron,

or even elephant bird, rhinoceros egret.[19] Its Arabic name, abu qerdan, means "father of ticks", a name derived from the huge number of parasites such as avian ticks found in its breeding colonies.[19][57]

A conspicuous species, the cattle egret has attracted many common names.

These mostly relate to its habit of following cattle and other large

animals, and it is known variously as cow crane, cow bird or cow heron,

or even elephant bird, rhinoceros egret.[19] Its Arabic name, abu qerdan, means "father of ticks", a name derived from the huge number of parasites such as avian ticks found in its breeding colonies.[19][57]

The cattle egret is a popular bird with cattle ranchers for its perceived role as a biocontrol of cattle parasites such as ticks and flies.[19] A study in Australia found that cattle egrets reduced the number of flies that bothered cattle by pecking them directly off the skin.[58] It was the benefit to stock that prompted ranchers and the Hawaiian Board of Agriculture and Forestry to release the species in Hawaii.[30][59][60]

Not all interactions between humans and cattle egrets are beneficial. The cattle egret can be a safety hazard to aircraft due to its habit of feeding in large groups in the grassy verges of airports,[61] and it has been implicated in the spread of animal infections such as heartwater, infectious bursal disease[62] and possibly Newcastle disease.[63][64]

It is a white bird adorned with buff plumes in the breeding season. It nests in colonies, usually near bodies of water and often with other wading birds. The nest is a platform of sticks in trees or shrubs. Cattle egrets exploit drier and open habitats more than other heron species. Their feeding habitats include seasonally inundated grasslands, pastures, farmlands, wetlands and rice paddies. They often accompany cattle or other large mammals, catching insect and small vertebrate prey disturbed by these animals. Some populations of the cattle egret are migratory and others show post-breeding dispersal.

The adult cattle egret has few predators, but birds or mammals may raid its nests, and chicks may be lost to starvation, calcium deficiency or disturbance from other large birds. This species maintains a special relationship with cattle, which extends to other large grazing mammals; wider human farming is believed to be a major cause of their suddenly expanded range. The cattle egret removes ticks and flies from cattle and consumes them. This benefits both species, but it has been implicated in the spread of tick-borne animal diseases.

Contents

Taxonomy[edit]

The cattle egret has two geographical races which are sometimes classified as full species, the western cattle egret, B. ibis, and eastern cattle egret, B. coromandus. The two forms were split by McAllan and Bruce,[6] but were regarded as conspecific by almost all other recent authors until the publication of the influential Birds of South Asia.[7] The eastern subspecies B. (i.) coromandus, described by Pieter Boddaert in 1783, breeds in Asia and Australasia, and the western nominate form occupies the rest of the species range, including the Americas.[8] Some authorities recognise a third Seychelles subspecies, B. i. seychellarum, which was first described by Finn Salomonsen in 1934.[9]

Despite superficial similarities in appearance, the cattle egret is more closely related to the genus Ardea, which comprises the great or typical herons and the great egret (A. alba), than to the majority of species termed egrets in the genus Egretta.[10] Rare cases of hybridization with little blue herons Egretta caerulea, little egrets Egretta garzetta and snowy egrets Egretta thula have been recorded.[11]

Description[edit]

The cattle egret is a stocky heron with an 88–96 cm (35–38 in) wingspan; it is 46–56 cm (18–22 in) long and weighs 270–512 g (9.5–18.1 oz).[12] It has a relatively short thick neck, a sturdy bill, and a hunched posture. The non-breeding adult has mainly white plumage, a yellow bill and greyish-yellow legs. During the breeding season, adults of the nominate western subspecies develop orange-buff plumes on the back, breast and crown, and the bill, legs and irises become bright red for a brief period prior to pairing.[13] The sexes are similar, but the male is marginally larger and has slightly longer breeding plumes than the female; juvenile birds lack coloured plumes and have a black bill.[12][14]B. i. coromandus differs from the nominate subspecies in breeding plumage, when the buff colour on its head extends to the cheeks and throat, and the plumes are more golden in colour. This subspecies' bill and tarsus are longer on average than in B. i. ibis.[15] B. i. seychellarum is smaller and shorter-winged than the other forms. It has white cheeks and throat, like B. i. ibis, but the nuptial plumes are golden, as with B. i. coromandus.[9]

The positioning of the egret's eyes allows for binocular vision during feeding,[16] and physiological studies suggest that the species may be capable of crepuscular or nocturnal activity.[17] Adapted to foraging on land, they have lost the ability possessed by their wetland relatives to accurately correct for light refraction by water.[18]

This species gives a quiet, throaty rick-rack call at the breeding colony, but is otherwise largely silent.[19]

Distribution and habitat[edit]

Flock over typical grassland habitat in Kolkata.

The species first arrived in North America in 1941 (these early sightings were originally dismissed as escapees), bred in Florida in 1953, and spread rapidly, breeding for the first time in Canada in 1962.[20] It is now commonly seen as far west as California. It was first recorded breeding in Cuba in 1957, in Costa Rica in 1958, and in Mexico in 1963, although it was probably established before that.[21] In Europe, the species had historically declined in Spain and Portugal, but in the latter part of the 20th century it expanded back through the Iberian Peninsula, and then began to colonise other parts of Europe; southern France in 1958, northern France in 1981 and Italy in 1985.[20] Breeding in the United Kingdom was recorded for the first time in 2008 only a year after an influx seen in the previous year.[22][23] In 2008, cattle egrets were also reported as having moved into Ireland for the first time.[24]

In Australia, the colonisation began in the 1940s, with the species establishing itself in the north and east of the continent.[25] It began to regularly visit New Zealand in the 1960s. Since 1948 the cattle egret has been permanently resident in Israel. Prior to 1948 it was only a winter visitor.[26]

The massive and rapid expansion of the cattle egret's range is due to its relationship with humans and their domesticated animals. Originally adapted to a commensal relationship with large browsing animals, it was easily able to switch to domesticated cattle and horses. As the keeping of livestock spread throughout the world, the cattle egret was able to occupy otherwise empty niches.[27] Many populations of cattle egrets are highly migratory and dispersive,[19] and this has helped the species' range expansion. The species has been seen as a vagrant in various sub-Antarctic islands, including South Georgia, Marion Island, the South Sandwich Islands and the South Orkney Islands.[28] A small flock of eight birds was also seen in Fiji in 2008.[29]

In addition to the natural expansion of its range, cattle egrets have been deliberately introduced into a few areas. The species was introduced to Hawaii in 1959, and to the Chagos Archipelago in 1955. Successful releases were also made in the Seychelles and Rodrigues, but attempts to introduce the species to Mauritius failed. Numerous birds were also released by Whipsnade Zoo in England, but the species was never established.[30]

Although the cattle egret sometimes feeds in shallow water, unlike most herons it is typically found in fields and dry grassy habitats, reflecting its greater dietary reliance on terrestrial insects rather than aquatic prey.[31]

Migration and movements[edit]

Flying in Dallas with a twig in its beak for its nest.